Latent Geometry

ature is comprised of geometrical patterns. "This process gives rise to har-mony, which may be defined as the relation between parts and unity, the simplicity latent in the infinitely complex, the potential complexity of that which is simple."

The word "latent" intrigues me. In fact, it is the purpose of this whole site - to acknowledge, find and work with what is hidden. All of the information we will need will not be obvious. If we looked for the riddles that people created to protect valuable, empowering information, it was never in plain sight. We had to work for it.

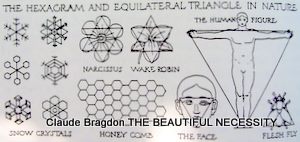

"Latent Geometry" from The Beautiful Necessity by Greg Bragdon, FAIA

[Illustration 51: THE HEXAGRAM AND EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE IN NATURE]

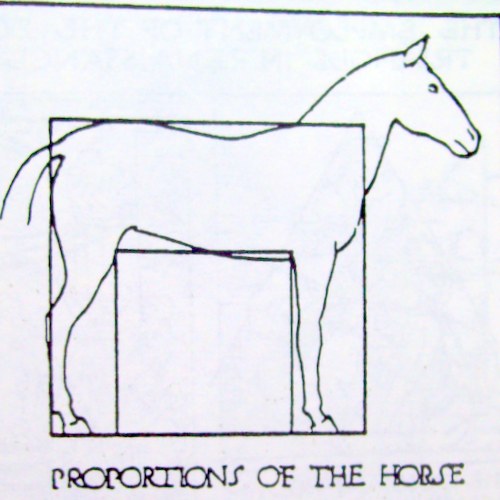

It is a well known fact that in the microscopically minute of nature, units every-where tend to arrange themselves with relation to certain simple geometrical solids, among which are the tetrahedron, the cube, and the sphere. This process gives rise to harmony, which may be defined as the relation between parts and unity, the simplicity latent in the infinitely complex, the potential complexity of that which is simple. Proceeding to things visible and tangible, this indwelling harmony, rhythm, proportion, which has its basis in geometry and number, is seen to exist in crystals, flower forms, leaf groups, and the like, where it is obvious; and in the more highly organized world of the animal kingdom also; though here the geometry is latent rather than patent, eluding though not quite defying analysis, and thus augmenting beauty, which like a woman is alluring in proportion as she eludes (Illustrations 51, 52, 53).

[Illustration 52: PROPORTIONS OF THE HORSE]

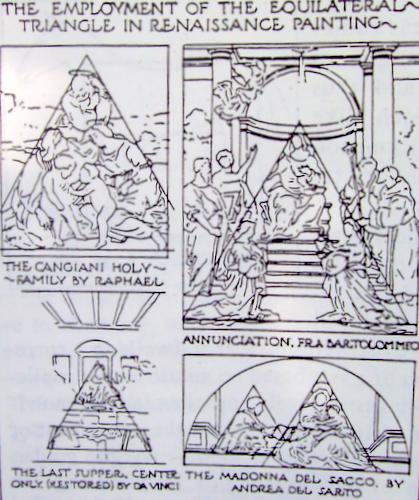

By the true artist, in the crystal mirror of whose mind the universal harmony is focused and reflected, this secret of the cause and source of rhythm--that it dwells in a correlation of parts based on an ultimate simplicity--is instinctively apprehended. A knowledge of it formed part of the equipment of the painters who made glorious the golden noon of pictorial art in Italy during the Renaissance. The problem which preoccupied them was, as Symonds says of Leonardo, "to submit the freest play of form to simple figures of geometry in grouping." Alberti held that the painter should above all things have mastered geometry, and it is known that the study of perspective and kindred subjects was widespread and popular.

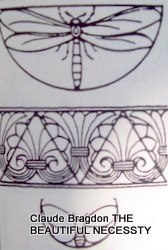

Illustration 53

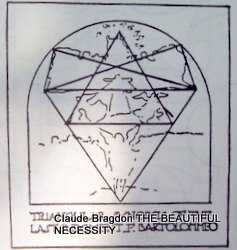

[Illustration 54] Triangulation of The Last Judgment F. Bartolomeo

The Last Judgment by F. Bartolomeo

The first painter who deliberately rather than instinctively based his compo-sitions on geometrical principles seems to have been Fra Bartolommeo, in his Last Judgment, in the church of St. Maria Nuova, in Florence. Symonds says of this picture, "Simple figures--the pyramid and triangle, upright, inverted, and interwoven like the rhymes of a sonnet--form the basis of the composi-tion. This system was adhered to by the Fratre in all his subsequent works" (Illustration 54). Raphael, with that power of assimilation which distinguishes

him among men of genius, learned from Fra Bartolommeo this method of disposing figures and combining them in masses with almost mathematical precision. It would have been indeed surprising if Leonardo da Vinci, in whom the artist and the man of science were so wonderfully united, had not been greatly preoccupied with the mathematics of the art of painting.

Madonna of the Rocks by Leonardo da Vinci

His Madonna of the Rocks, and Virgin on the Lap of Saint Anne, in the Louvre, exhibit the very perfection of pyramidal composition. It is however in his masterpiece, The Last Supper, that he combines geometrical symmetry and precision with perfect naturalness and freedom in the grouping of individually interesting and dramatic figures. Michael Angelo, Andrea del Sarto, and the great Venetians, in whose work the art of painting may be said

to have culminated, recognized and obeyed those mathematical laws of composition known to their immediate predecessors, and the decadence of the art in the ensuing period may be traced not alone to the false sentiment and affectation of the times, but also in the abandonment by the artists of those obscurely geometrical arrangements and groupings which in the works of the greatest masters so satisfy the eye and haunt the memory of the beholder (Illustrations 55, 56).

Illustration 55: THE EMPLOYMENT OF THE EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE IN

RENAISSANCE PAINTING

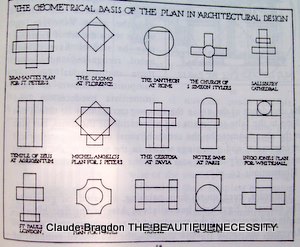

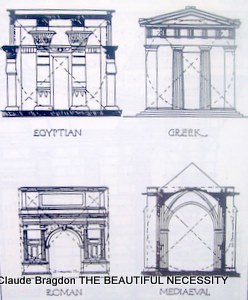

Sculpture, even more than painting, is based on geometry. The colossi of Egypt, the bas-reliefs of Assyria, the figured pediments and metopes of the temples of Greece, the carved tombs of Revenna, the Della Robbia lunettes, the sculptured tympani of Gothic church portals, all alike lend themselves in greater or less degree to a geometrical synopsis (Illustration 57). Whenever sculpture suffered divorce from architecture the geometrical element became less prominent, doubtless because of all the arts architecture is the most clearly and closely related to geometry. Indeed, it may be said that architecture is geometry made visible, in the same sense that music is number made audible. A building is an aggregation of the commonest geo-metrical forms: parallelograms, prisms, pyramids and cones--the cylinder appearing in the column, and the hemisphere in the dome. The plans likewise of the world's famous buildings reduced to their simplest expression are discovered to resolve themselves into a few simple geometrical figures. (Illustration 58). This is the "bed rock" of all excellent design.

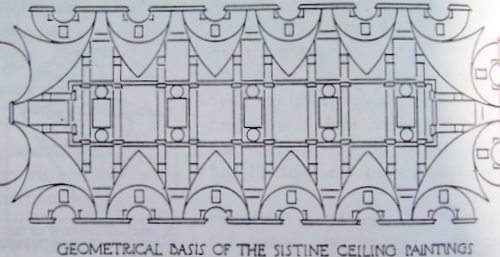

Illustration 56 - Geometrical Basis of the Sistine Ceiling Paintings

[Illustration 58: THE GEOMETRICAL BASIS OF THE PLAN IN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN]

But architecture is geometrical in another and a higher sense than this. Emerson says: "The pleasure a palace or a temple gives the eye is that an order and a method has been communicated to stones, so that they speak and geometrize, become tender or sublime with expression." All truly great and beautiful works of architecture from the Egyptian pyramids to the cathedrals of Ile-de-France--are harmoniously proportioned, their principal and subsidiary masses being related, sometimes obviously, more often obscurely, to certain symmetrical figures of geometry, which though invisible to the sight and not consciously present in the mind of the beholder, yet perform the important function of coordinating the entire fabric into one easily remembered whole. Upon some such principle is surely founded what Symonds calls "that severe and lofty art of composition which seeks the highest beauty of design in architectural harmony supreme, above the melodies of gracefulness of detail."

Illustration 59

Illustration 60

Thought detail by Allison L. Williams Hill

[Illustration 61: JEFFERSON'S PEN SKETCH FOR THE ROTUNDA OF THE

UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA]

There is abundant evidence in support of the theory that the builders of antiquity, the masonic guilds of the Middle Ages, and the architects of the Italian Renaissance, knew and followed certain rules, but though this theory be denied or even disproved--if after all these men obtained their results unconsciously--their creations so lend themselves to a geometrical analysis that the claim for the existence of certain canons of proportion, based on geometry, remains unimpeached.

Links