Modern Cities

Part I from The Higher World from The Hidden Side of Things by C.W. Leadbeater

Just as our ancestors of long ago lived their ordinary lives in what was to them the ordinary commonplace way, and never dreamed that in doing so they were impregnating the stones of their city walls with influences which would enable a psychometer thousands of years afterwards to study the inmost secrets of their existence, so we ourselves are impregnating our cities and leaving behind us a record which will shock the sensibilities of the more developed men of the future. In certain ways which will readily suggest themselves, all great towns are much alike; but on the other hand there are differences of local atmosphere, depending to some extent upon the average morality of the city, the type of religious views most largely held in it, and its principal trades and manufactures.

Philadelphia, PA 2021

For all these reasons each city has a certain amount of individuality-- and individuality which will attract some people and repel others, according to their disposition. Even those who are not specially sensitive can hardly fail to note the distinction between the feeling of Paris and that of London, between Edinburgh and Glasgow, or between Philadelphia and Chicago.

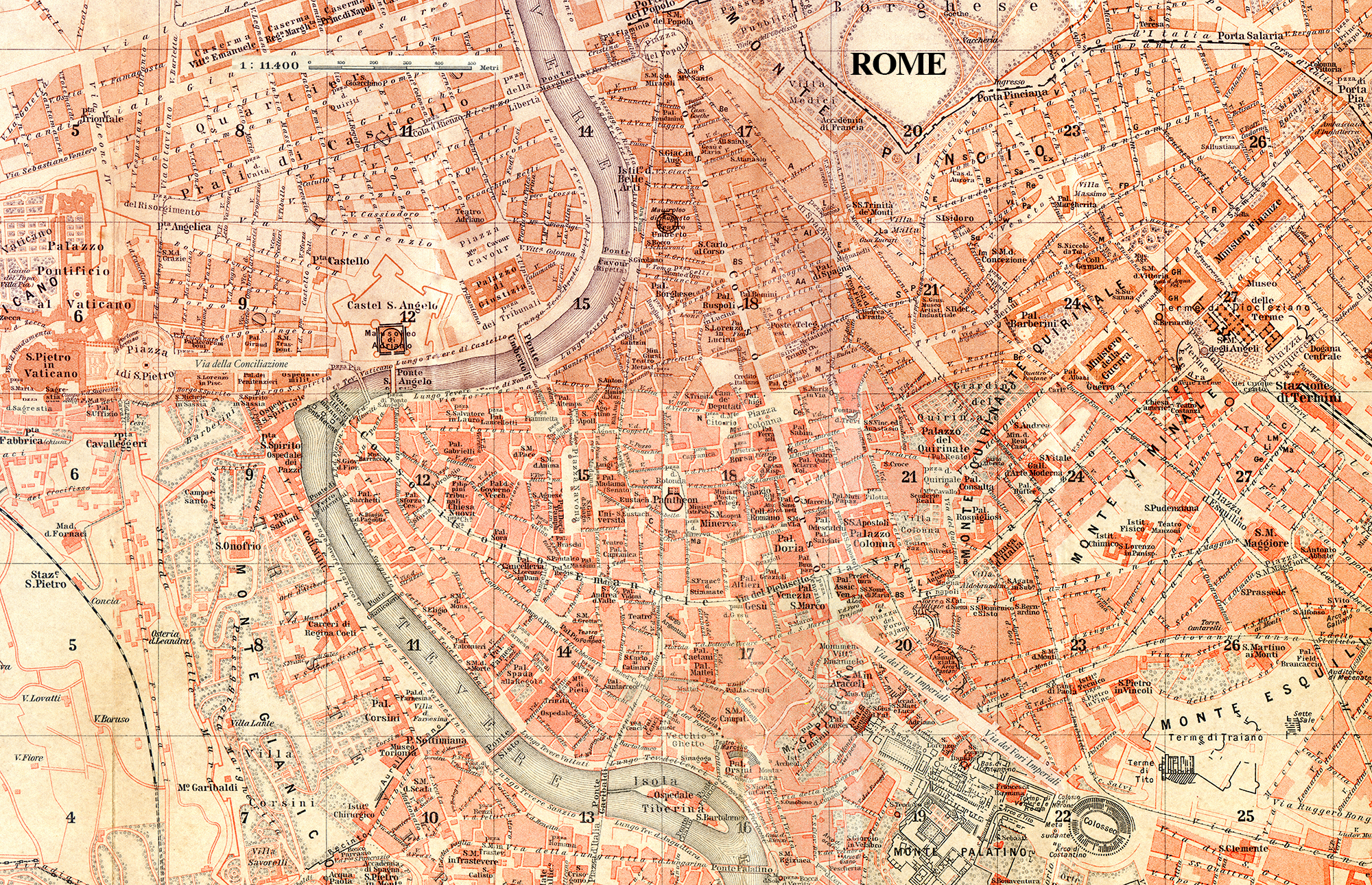

There are some cities whose key-note is not of the present but of the past--

whose life in earlier days was so much more forcible than it is now, that the present is dwarfed by its comparison. The cities on the Zuyder Zee in Holland are an instance of this; S. Albans in England is another. But the finest example which the world has to offer is the immortal city of Rome. Rome stands alone among the cities of the world in having three great and entirely separate interests for the psychic investigator. First, and much the strongest, is the impression left by the astonishing vitality and vigour of that Rome which was the centre of the world, the Rome of the Republic and the Caesars; then comes another strong and unique impression-- that of mediaeval Rome, the ecclesiastical centre of the world: third and quite different from either, the modern Rome of to-day, the political centre of the somewhat loosely integrated Italian kingdom, and at the same time still an ecclesiastical centre of widespread influence, though shorn of its glory and power.

I first went to Rome, I confess, with the expectation that the Rome of the mediaeval Popes, with the assistance of all the world-thought that must for so long have been centred upon it, and with the advantage also of being so much nearer to us in time, would have to a considerable extent blotted out the life of the Rome of the Caesars. I was startled to find that the actual facts are almost exactly the reverse of that. The conditions of Rome in the Middle Ages were sufficiently remarkable to have stamped an indelible character upon any other town in the world; but so enormously stronger was the amazingly vivid life of that earlier civilisation, that it still stands out, in spite of all the history that has been made there since, as the one ineffaceable and dominating characteristic of Rome.

To the clairvoyant investigator, Rome is (and ever will be) first of all the Rome of the Caesars, and only secondarily the Rome of the Popes. The impression of ecclesiastical history is all there, recoverable to the minutest detail; a bewildering mass of devotion and intrigue, of insolent tyranny and real religious feeling; a history of terrible corruption and of world-wide power, but rarely used as well as it might have been. And yet, mighty as it is, it is dwarfed into absolute insignificance by the grander power that went before it. There was a robustness of faith in himself, a conviction of destiny, a resolute intention to live his life to the utmost, and a certainty of being able to do it, about the ancient Roman, which few nationalities of to-day can approach.

Modern Cities' Public Buildings

Not only has a city as a whole its general characteristics, but such of the buildings in it as are devoted to special purposes have always an aura characteristic of that purpose. The aura of a hospital, for example, is a curious mixture; a preponderance of suffering, weariness and pain, but also a good deal of pity for the suffering, and a feeling of gratitude on the part of the patients for the kindly care which is taken of them.

The neighbourhood of a prison is decidedly to be avoided when a man is selecting a residence, for from it radiate the most terrible gloom and despair and settled depression, mingled with impotent rage, grief and hatred. Few places have on the whole a more unpleasant aura around them; and even in the general darkness there are often spots blacker than the rest, cells of unusual horror round which an evil reputation hangs. For example, there are several cases on record in which the successive occupants of a certain cell in a prison have all tried to commit suicide, those who were unsuccessful explaining that the idea of suicide persistently arose in their minds, and was steadily pressed upon them from without, until they were gradually brought into a condition in which there seemed to be no alternative. There have been instances in which such a feeling was due to the direct persuasion of a dead man; but also and more frequently it is simply that the first suicide has charged the cell so thoroughly with thoughts and suggestions of this nature that the later occupants, being probably persons of no great strength or development of will, have found themselves practically unable to resist.

More terrible still are the thoughts which still hang round some of the dreadful dungeons of mediaeval tyrannies, the oubliettes of Venice or the torture-dens of the Inquisition. Just in the same way the very walls of a gambling-house radiate grief, envy, despair and hatred, and those of the public-house, or house of ill-fame, absolutely reek with the coarsest forms of sensual and brutal desire.

In such cases as those mentioned above, it is easy enough for all decent

people to escape the pernicious influences simply by avoiding the place; but there are other instances in which people are placed in undesirable situations

through the indulgence of natural good feeling. In countries which are

not civilised enough to burn their dead, survivors constantly haunt the

graves in which decaying physical bodies are laid; from a feeling of

affectionate remembrance they gather often to pray and meditate there,

and to lay wreaths of flowers upon the tombs. They do not understand

that the radiations of sorrow, depression and helplessness which so

frequently permeate the churchyard or cemetery make it an eminently undesirable place to visit.

I have seen old people walking and sitting about in some of our more beautiful cemeteries, and nursemaids wheeling along young children in their perambulators to take their daily airing, neither of them probably having the least idea that they are subjecting themselves and their charges to influences which will most likely neutralise all the good of the exercise and the fresh air; and this quite apart from the possibility of unhealthy physical exhalations.

Links

The above meditation mandala will be available soon.